1796 (June 13) Fire

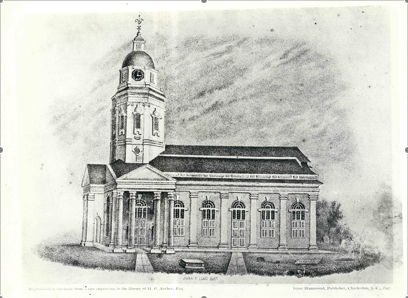

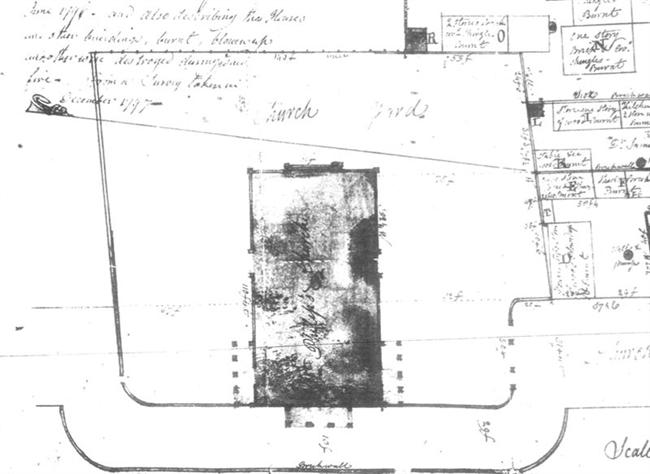

The fire of June 13-14, 1796, was discovered in Lodge Alley at three o'clock in the afternoon, and it burned until nearly dawn. With the wind blowing west from the river, the spread of the blaze defied firefighters' pump-wagons, ladders, and buckets. The fire was finally extinguished along Meeting Street. At daybreak began the tally of damages: from East Bay Street between Broad Street and Wragg's Alley [Cumberland Street] west to Meeting Street, more than 250 lots had been cleared of buildings. Because of the dense residential construction in this neighborhood, it was estimated that at least 300 families had been burned out. One of the fire's victims, a schoolmaster with the heroic name of Alexander Alexander, lost no time reorganizing his life. In a notice in the June 16 City Gazette, Alexander thanked his "numerous friends for their strenuous, though unsuccessful exertions to preserve his house and school in the late fire, as well as for their more fortunate endeavors to save his furniture and effects, several of which have not yet been returned, he supposes for want of knowing the place of his present residence, which is at Mr. Vale's in Guignard Street. Most of his wearing apparel and several other articles are yet missing. Other burned-out property owners filled the newspaper with advertisements seeking the return of furniture, clothing, carpenter's tools, and the inventory of their businesses. It was their good fortune that late-eighteenth century Charleston was, on the whole, a prosperous city. Residents unaffected by the fire eagerly donated to a relief fund managed by a committee of churchmen and civic leaders, who were "appointed to distribute the charitable contributions of the citizens among the sufferers by the late fire… to distribute the bounty of the citizens in a manner proportionate to the real circumstances of the sufferers." In number, buildings used as private residences and businesses were the large majority of the losses. However, some of the city's iconic institutional buildings were also destroyed. The Beef Market, at the corner of Broad and Meeting streets, was ruined, its site later cleared for construction of a branch of the Bank of the United States (today's 80 Broad Street, Charleston City Hall). Charles Fraser, writing in 1854, still mourned the loss of "the original French church, where the Huguenot refugees had worshipped for upwards of a century previous to that time. But the most memorable building destroyed by it, was the old City Tavern, which stood at the northeast corner of Church and Broad streets, noted in our social and political annals, as having given its name to the old Corner Club, where the forefathers of so many of the present generation used to meet of an evening, to smoke their pipes, and talk over the topics of the day…” The City Tavern building had housed a succession of such businesses, including Shepheard's and Dillon's taverns. Its corner lot, 46 Broad Street, is occupied by a twentieth century bank building. Charles Fraser also related the tale of the rescue of St. Philip's Church. The fire "would have destroyed that venerable building but for the heroic intrepidity of a negro, who, at the risk of his life, climbed to the very summit of the belfry, and tore off the burning shingles." St. Philip's vestry minutes tell this "negro's" story. His name given only as Will, he was a slave belonging to Charles Lining, a church vestryman. On August 14, 1796, two months after the fire, St. Philip's vestry voted to reward Will by making him a free man. The next month, they paid $707.14 to Charles Lining for "his fellow, Will," and freed Will legally with a deed of manumission. The scale of the June fire was immense, so much so that a blaze barely a month earlier has nearly been forgotten. On May 16, 1796 the Columbian Herald reported that the previous Saturday at about 2:00 AM, fire broke out in the house of Mr. Lyon Moses in King Street, spread to an adjacent building, and "in a short time, exhibited a dreadful spectacle of conflagration." Among more than sixty dwelling houses and residential tenements destroyed on King and Beresford [Fulton] streets was the "celebrated inn" called Martin's Tavern, kept by Mr. Brockway. Spectacular fires were frequent enough; smaller blazes were almost routine. On the afternoon of July 18, 1796, a fire broke out in the roof of Mrs. Ravenel's dwelling house on Meeting Street. The firemasters, "finding their utmost exertions to save it in vain, had it pulled down, to prevent its communicating to the adjacent buildings." City Gazette, various dates.

|