69. Old Powder Magazine 1712

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ |

|

| . |

|

The Old Powder Magazine on Cumberland Street, the oldest public building in Charleston, was constructed toward the end of the Lords Proprietors' rule over South Carolina. A tourist attraction since the nineteenth century, the building was purchased in 1902 by the National Society of Colonial Dames in South Carolina, and restored in 1993 by Historic Charleston Foundation. It is maintained as a public historic site.

Gunpowder storage was a troublesome business from Charleston's first settlement into the early twentieth century, requiring public officials to juggle issues of accessibility and oversight against safety and economy. The gunpowder provided by the Lords Proprietors was typically scattered in several safe locations; for instance, in 1671 the Grand Council resolved that the store of powder should be divided into three parts. Six barrels were to be kept in the custody of Capt. John Godfrey, three in Sir John Yeamans's house in town, and three in the Lords Proprietors' storehouse. During the next century and a half, civic leaders continued an uneasy relationship with their dangerous necessity.

In 1703, the Commons House of Assembly authorized construction of a brick magazine or powder house inside Charleston's fortification wall. This was not done for several years. Public ammunition and powder were still being kept in various bastions along the defensive curtain wall in 1712, when £50 was allotted from the public treasury to build a powder magazine, which was completed in 1713. However, it was not weathertight, and did not keep powder acceptably dry. The roof was eventually reworked, and in 1718, an Act of Assembly stipulated that "no person whatsoever, shall keep in a house in Charles Town, more than one-quarter of a barrel of powder." From that date, the Powder Magazine became the repository of all government-owned powder, as well as supplies held by merchants for sale.

Except the line of fortifications along the Cooper River, Charleston's defensive walls were gradually dismanteled as the town grew to the north, west, and south. With this growth came the decision to build a powder magazine in a less populous area. In 1737 the new magazine was built on the "Old Burying Ground," the block bounded by today's Queen, Franklin, Logan and Magazine streets. Poorly built and structurally inadequate, it was abandoned within a few years, and the gunpowder supply was returned to the Old Powder Magazine. Despite ongoing objections to the storage of explosives between two principal houses of worship (St. Philip's Church and the White Meeting House), and near the centers of trade and shipping, gunpowder was kept in the Old Powder Magazine until 1748. In that year, an adequate replacement magazine was finally completed on public land near the site of the 1737 storehouse.

Along with the demand for removing hazardous material from the Old Powder Magazine in the interest of public safety, beginning in 1741 came a series of petitions from the owners of the property on which it stood. Ralph Izard, Nathaniel Broughton, and Paul Mazyck petitioned the Grand Council and Commons House of Assembly that they were the owners of Town Lot 180, where the Powder Magazine had been built. The government agreed to build another magazine, remove the existing structure, and restore the property to the petitioners. This was not done, and the petition was renewed in 1745. The General Assembly agreed to pay rent to the land owners as long as the gunpowder storehouse remained on their property.

The powder magazine was never removed, either by the government or by private parties. Ownership remained in Ralph Izard's family, passing to his daughter Margaret Izard [Mrs. Gabriel Manigault], to her son Charles Izard Manigault (1795-1874), and finally to Dr. Gabriel E. Manigault (1833-1899).

During the American Revolution, the Old Powder magazine was returned to its original purpose. In March, 1780, preparing for the British attack, Charleston's Powder Receiver paid Richard Peronneau £286.15.0 for "boards and carpenters work to repair the Magazine behind the old Church." After a near disaster, when a British shell burst nearby on May 7, General William Moultrie emptied its contents, writing in his Memoirs, "In consequence of that shell falling so near, I had the powder (100,000 pounds) removed to the northeast corner under the Exchange, and had the doors and windows bricked up. Not withstanding the British had possession of Charleston so long, they never discovered the powder, although their Provost was the next apartment to it, and after the evacuation when we came into town we found the powder as we left it."

The empty structure was eventually reclaimed by the Manigault family, although it was used again for public powder storage for a brief time in 1820. Over time, the interior was partitioned for a variety of purposes, from wine storage to a commercial printing press. The vacant building was described in the News and Courier on January 10, 1897, in unstable condition, "gradually falling to pieces." Dr. Gabriel Manigault told the newspaper's editor that he felt the "time has almost come when it must be removed altogether."

The Old Powder Magazine was not demolished, and in 1902 the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of South Carolina bought it and made essential repairs. In 1993, the Colonial Dames leased the building to Historic Charleston Foundation for ten years. The Foundation undertook a complete renovation directed by architect Glenn Keyes, and returned the Old Powder Magazine to the Colonial Dames in 2003. Behre, Robert. "Building loses its patina for the good." News and Courier, June 23, 2003.

Behre, Robert. "Magazine due repairs." News and Courier, July 25, 1993.

Davis, Nora M. "Public Powder Magazines at Charleston." City of Charleston Yearbook, 1942.

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of the American Revolution. Vol. 2. New York, 1802; rep. ed. Arno Press, 1968.

"Powder Magazine has face lifted." News and Courier, March 6, 1967.

"Quaint Structure… Was Saved from Decay by Dawson's Suggestion." News and Courier, March 9, 1936.

Zierden, Martha A., et. al. "Archaeology at the Powder Magazine: A Charleston Site through Three Centuries (38Ch97)." Charleston: The Charleston Museum Archaeological Contributions 26, prepared for Historic Charleston Foundation, 1997.

|

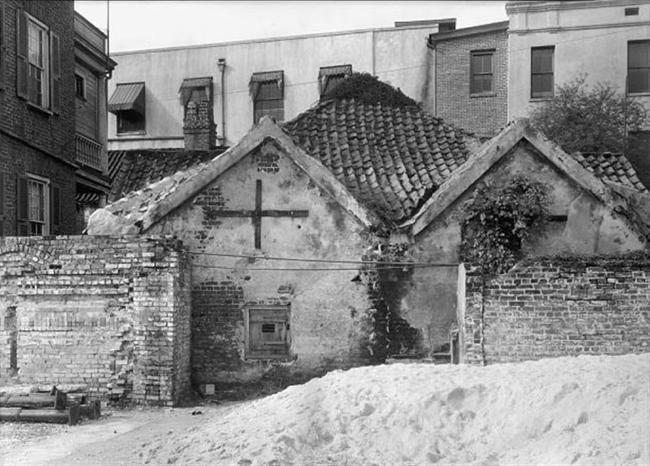

| American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ |

"Old Powder Magazine," ca. 1902.

|

| |

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ |

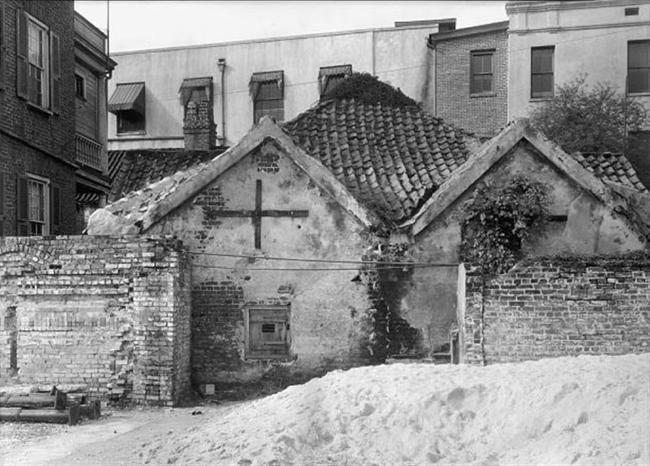

| Old Powder Magazine, April 1940 |

| |

|

| Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures |

Old Powder Magazine, 1937.

|

| |

|

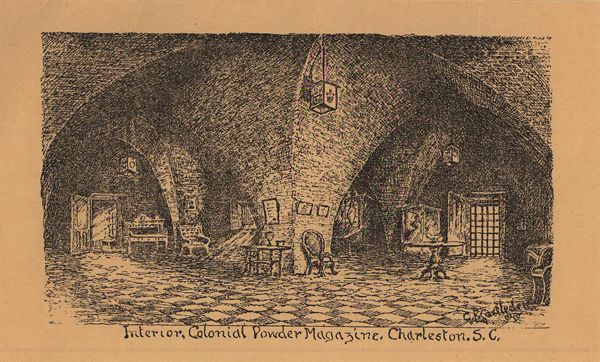

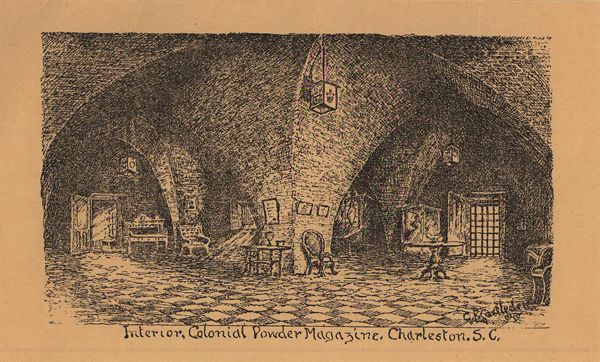

| George F. Castleden's Studio, Charleston, S.C., 1935. |

| With three-foot thick brick walls, the Powder Magazine was designed to protect its contents from fire, dampness, and theft, while containing any accidental explosions within the structure. Support for the heavy tiled roof was provided by groin vaults and a central brick column. |

| |

|

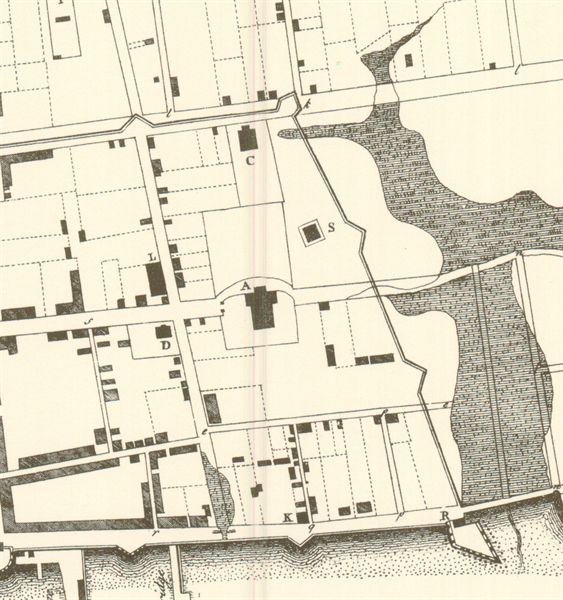

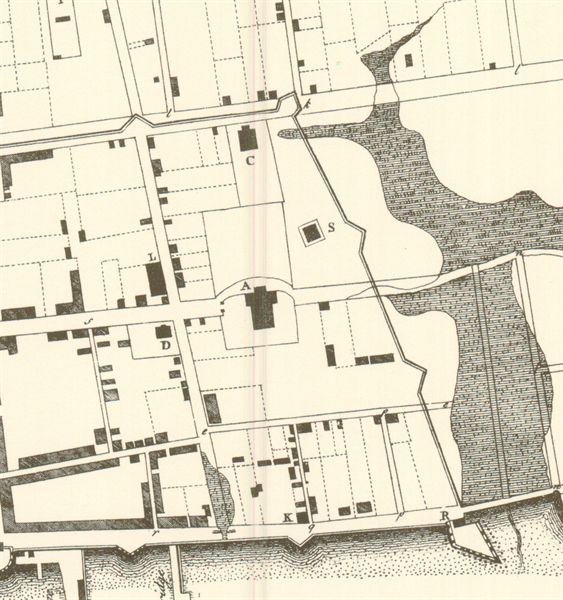

| Bishop Roberts and W. H. Toms, The Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water. London, 1739. |

| Shown on Bishop Roberts' 1739 map as "S," the Powder Magazine was inside Charleston's fortification wall. |

| |

|