Battle of Sullivan's Island, June 28, 1776

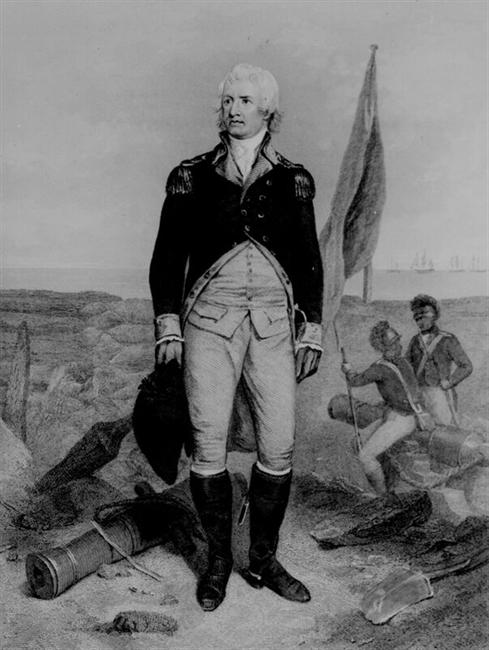

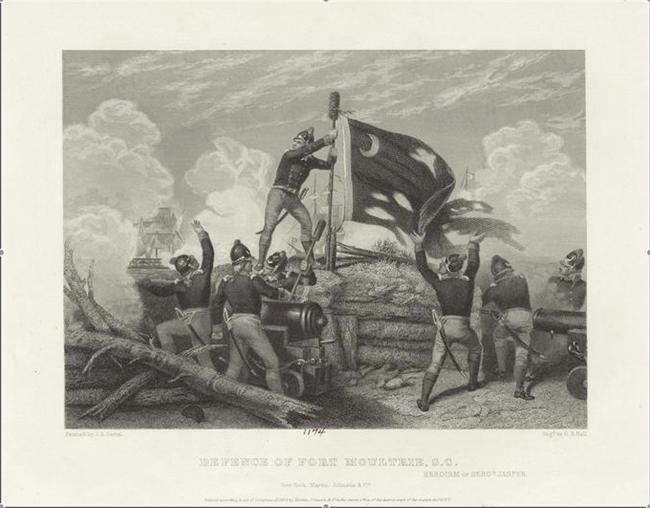

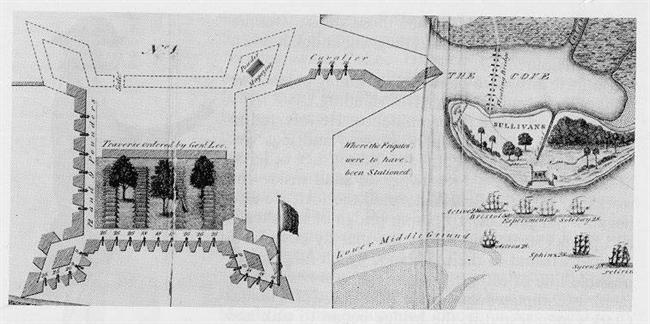

The Battle of Sullivan's Island, June 28, 1776, was the mighty British navy's first test in southern waters. Nine warships mounting nearly 270 guns (cannon) were soundly defeated by Colonel William Moultrie and about 400 Continental soldiers defending an uncompleted fort. The British intended to take Sullivan's Island, then use it as a base for overcoming Charleston Harbor and the city. They planned a two-pronged attack, with a landing force of 2,500 redcoats under General Sir Henry Clinton's army sailing with Commodore Sir Peter Parker's men-of-war. Lord William Campbell, South Carolina’s last royal governor, was aboard Parker’s flagship, HMS Bristol, where he commanded a gundeck. While the British navy pounded the fort at the south tip of the island, troops under Clinton and Lord Charles Cornwallis would land small boats on the Isle of Palms, cross Breach Inlet, and attack Moultrie's garrison from the rear. Col. Moultrie was at Breach Inlet on the morning of June 28, visiting the advance guard encamped there. He saw the British boats and men-of-war in motion, and raced his horse back to the unnamed fort at the other end of the island. Moultrie's square fort had 500' long double walls, ten feet high and sixteen feet apart, filled with sand, and punctuated by embrasures (openings for the guns); construction of the rear (landward) portion had not been completed. When the British began firing, the Continentals had thirty-one cannon, and less than thirty rounds of powder. Moultrie's orders were not to waste fire, and "never did men fight more bravely, and never were men more cool." During the day, boats delivered supplies of gunpowder from Charleston and Mount Pleasant, but there was still too little for comfort. At one point, Moultrie stopped firing entirely, reserving powder for the muskets that would be needed against a land attack. However, Clinton's army failed to cross Breach Inlet, defeated by the treacherous tides and American infantry. The battle of Sullivan's Island lasted nearly ten hours. The British cannon had no effect on the earth-filled palmetto log walls of the fort; only the shots that came above the wall or through the embrasures took any lives. Thousands of people, both civilians and militia, observed the action from Charleston, standing along the Cooper River or beneath lookouts perched on high roofs. Early in the day, a cannonball broke the mast of the fort's flag, and it fell from view. Agonized spectators feared the Americans had struck the flag and given up the defense. According to Moultrie, Sergeant William Jasper "jumped from one of the embrasures, and brought it up through a heavy fire, fixed it upon a staff, and planted it upon the ramparts again," visible to the onlookers several miles away. William Moultrie's men continued firing even after sunset, listening as their shots hit the British ships. Finally, Parker called a retreat and moved his ships out of range; Moultrie sent a dispatch boat to inform those in town that the navy had retired. For several days, the colonel and his garrison remained on Sullivan's Island, prepared for the return of the British and basking in their victory. Major General Charles Lee, commander of American forces in the south, sent a hasty note the morning after the battle: "I do most heartily thank you all… I have applied for some rum for your men. They deserve every comfort that can be afforded them." Others came in person with their good wishes. Governor Rutledge presented Sergeant Jasper with a sword in recognition of his gallant behavior, and William Logan delivered a "hogshead of old Antigua rum" for the officers and soldiers. Christopher Gadsden, stationed at Fort Johnson (James Island) sent Moultrie his enthusiastic congratulations for the "drubbing you gave those fellows the other day." Nevertheless, for more than a week the Continental officers in Charleston watched to see whether the British would renew their effort. Eventually, on July 7, General Lee requested Colonel Moultrie to "come to town as soon as he thinks proper." After the battle, the fort at Sullivan's Island was completed, and named Fort Moultrie. William Moultrie (1730-1805) served in the Continental Army until the end of the war, retiring with the rank of major general. He served two terms as governor of South Carolina before retiring to his plantation in St. John's, Berkeley, Parish. Sergeant William Jasper was killed in action against the British near Savannah on October 9, 1779. Davis, Robert S. "Jasper, William." Walter Edgar, ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006.

|

_650x650.jpg)